By Chris Rennirt

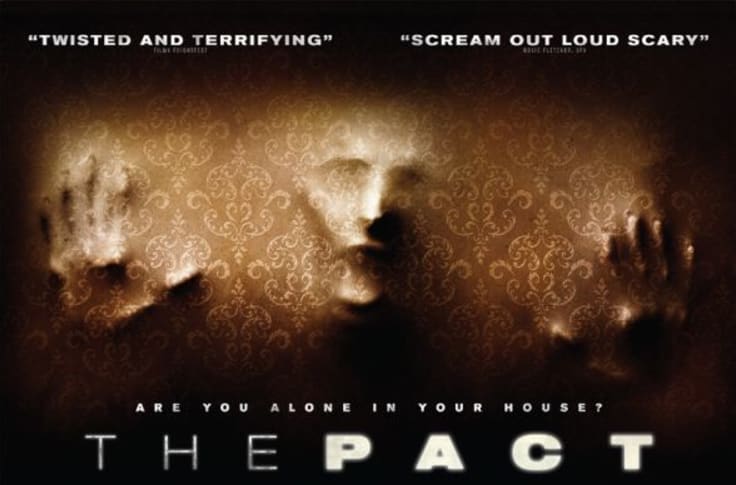

I am always a little bothered in the end, when I learn that the title of a movie has nothing to do with the movie. The Pact is just such a film that had me confused in the end, trying to figure it out. Realizing that, save for the most vague association by a stretch, the title means nothing, I gave up, less disappointed than possible for one reason only. The Pact was, despite its disconnected title, another hidden gem of horror, unknown by most would-be fans. I actually bought the DVD on impulse back in 2012, compelled by the box art and plot blurb alone, and just got around to watching it in 2021, nine years later! Genuinely creepy it was, all those years later. Getting under your skin and in your brain, viscerally as much as mentally, it’s one to put on your list, if you haven’t seen it already. It’s also one, as I now know, not to leave on the shelf for nearly a decade. If you’re like me, in the end you’ll be thinking of another title for it.

Jewell Staite (as Annie) in the 2011 short film, The Pact

The Pact is an independent horror film produced in 2012, based on an 11-minute short film produced in the previous year, by the same writer/director, Nicholas McCarthy. The short stars Jewell Staite and Sam Ball. Both films involve, as a basic plot in common, a woman coming to terms with the death of her mother, along with very strange, supernatural events that begin to haunt her, as she stays in her mother’s house. Even though it sounds generic, like everything you’ve already seen, it isn’t. Is it all otherworldly spirits hell-bent on revenge and chaos, or is it something more mortal, but just as deadly, in the physical world? Does a seemingly ordinary plot become something far from ordinary? The Pact (2011 and 2012) is a movie with such questions left unanswered here, with further plot details untold.

“…the short is all about not seeing things; it’s all about what’s hidden and what’s implied.” ~ Writer/Director Nicholas McCarthy

The writer/director says (in the movie’s behind-the-scenes, bluray featurette), that when The Pact premiered at the film festivals as a short film, he could see the effect it had on audiences–that it really scared them, and they wanted more. After only three days at the Sundance Film Festival, McCarthy got to work on a feature-length version, with what he described as only one major challenge–adding to it enough extra story to make it feature length; adding to it without it seeming contrived and stuffed, without it seeming just for the purpose of making it a feature. But was he successful? Does the longer version live up to the expectation, by comparison to its successful short? Does the feature film stand alone as the gem of lesser-known horror I’ve suggested already?

Caity Lotz (as Annie) in the 2012 feature-length film, The Pact

Fortunately, the film’s 11-minute short-film precursor remains on Youtube, and I’ve watched it myself and included it below. As for immediate differences, Nichole’s male sibling (played by Sam Ball) is replaced by a female sibling, Annie, (Caity Lotz), and that’s not a big deal, perse. An excellent choice is the inclusion of key scenes and even select dialogue from the short. Chilling examples involve a perceived touch on the neck, a camera panning upward to a flickering kitchen light, and a walk into a dark room–all ultra spooky, among only a few of the short’s best parts transferred to the feature. Indeed, as is not the the case in some short-to-feature productions, some of the best scenes from the short were, rather than discarded, used with full and equal effect in the feature film. A great choice, indeed!

Casper Van Dien (as Detective Creek)

Beyond that, the story expands comprehensively, filling in every hole the short created. As director Nicholas McCarthy says (in the film’s behind-the-scenes featurette), “the short is all about not seeing things; it’s all about what’s hidden and what’s implied,” thus, he decided that the feature would be about “seeing things.” It is, as he says, “like peeling back an onion,” and seeing all of the layers. And it is in this peeling of the onion that the movie suffers most. Sometimes it’s the unsolved mystery, lingering and expanding in the mind, that makes a movie remembered, ultimately better, and, in the case of horror, scarier. Sometimes, less is a lot better, as food for the mind, as the best generator of dread and fear. In a longer version, there can be too much time to do the fatal thing–to answer too many questions. While the short leaves things wide open for the mind to imagine, the feature, I think, narrows it down too much. In The Pact, we get a balance of both worlds–the real and the supernatural–but is that what we really want? Do we really need to see someone levitated and spinning in the air to be scared? Is that what really scared the audience in 2011? Is that really what made audiences want a 79-minute extension? For me, the answer is NO; it was, instead, the absence of such tangible elements and definition that made The Pact (2011) a film with greater impact.

Annie (Caity Lotz) finds someone (or something) not expected, in The Pact!

But, does that “NO” from me mean The Pact (2012) is a movie missing enough rockets to launch at SJR? My answer is NO again. A resounding NO, actually. Despite the fact that I learned more than I wanted to know–the fact that what I learned was not what I thought best for the story–I still liked the movie, and I still recommend it. Recommended also is watching the The Pact (2011) to see the difference for yourself. It is, indeed, a brave thing for a filmmaker to leave available the original short for a feature production. Along with it comes the risk of just such comparisons, not necessarily favorable and flattering to the feature. With this, I am reminded of the film Mama (2013), directed by Andy Muschietti. I reviewed the short film upon which it was based (also titled Mama) here on SJR prior to the feature’s production; later, it was removed from Youtube, and also from IMDb, with no trace of it ever existing. I also preferred the original short of Mama for many of the same reasons. So, all the smarter it was, perhaps, for Muschietti to remove the original for the chance of similar comparisons. But, I digress…just a little.

In The Pact, what hides in the dark is best left hidden.

Exactly what is scary about the short and the feature, when they are both at their best? Each has the element of the unknown, with the original addressing only the unknown, and the feature addressing what is at first unseen, ultimately revealing it all by the movie’s end. The Pact (2012) is most effective in the beginning, when it is most like the short film–when that touch on the neck, that silhouette in the dark, that blurry shape in the distance still have so many possibilities. Where did Nichole disappear to, so absolutely and utterly, walking in that dark room; the shift to total black is chilling and indelible. And, when Eva says, “Mommy, who is that behind you?” I recall few scenes in movies so scary.

Haley Hudson (as Stevie)

As for acting in both films, it is excellent. Caity Lotz nails the role of Annie, a character that never appears in the short. Again, Annie is the replacement for the character of Nichole’s brother in the short. Since Lotz is on screen in most of the movie’s running time, it is essential that she does the job so well. Otherwise, The Pact (2012) would have failed for lack of a key character’s believability. Lotz, as it mentioned by director Nicholas McCarthy, was a real trooper being thrown around so much in the movie! What I at first thought was a stunt double turns out to be the real Caity Lotz, with, as she describes, all of the “bruises and bumps” to prove it.

Haley Hudson (as Stevie)

Also adding to the movie’s crowd-pleasing credits is veteran actor Casper Van Dien (from Starship Troopers). Van Dien makes Creek–the feature film’s police detective counterpart–a standout character, rather than a forgettable cliche. Unlike many bigger-name actors in smaller-budget productions, Van Dien delivers more than perhaps the role expected, certainly making the movie better. Too often it is the ironic underperformances of veteran actors that add more negative than positive results. Not here!

“Is that a woman on the ceiling?” you ask. Indeed it is!

Also adding tremendously to film is Haley Hudson in the role of the blind, clairvoyant girl, Stevie. In the movie’s behind-the-scenes featurette (on the bluray), A Haunting in San Pedro: The Making of The Pact, director Nicholas McCarthy talks about how Hudson won the role of Stevie. He said she showed up for the audition in character, staying in character the whole time. McCarthy said that he wanted to talk to Hudson afterward, but “she wouldn’t stop being that person.” “Transfixed” by her, but also “a little afraid of her,” McCarthy knew she was the one for the role. Actor Caity Lotz recalls how Hudson would even “stay blind, having people help her walk through the set.” And Hudson’s self-immersion in the role pays off exponentially; as Stevie, she appears hypnotized with her persona, utterly authentic, looking the part physically, as much as acting it. If only more actors put as much into their roles, how much better more performances and movies would be!

Gratuitous foot nudity in The Pact makes a film Tarantino would enjoy, if not make himself. (Caity Lotz works on her motorcycle, among other things, barefoot, while the camera lingers.)

As a side note (and one that must be highlighted for its pretentiousness and frequency, as well as for its contrast with the short film), The Pact (2012) was definitely a wet dream of a movie for anyone with a foot fetish. Every woman in the movie is barefoot at some point, more or less, with Caity Lotz being the most–the highlight perhaps being her late-night walk to a soda machine at a Motel 8, barefoot in short shorts, and later riding a motorcycle with no shoes! Yes! This is a movie that rivals the most sole-bearing films that Quentin Tarantino has yet produced, directed, etc.–with Tarantino being the reigning king of it. (Check out and compare any of his films–particularly From Dusk Till Dawn, Pulp Fiction, Kill Bill, and especially Death Proof–with the feet of Syndney Tamiia Poitier–if you don’t believe me!) Likewise, in The Pact, every form of contrivance is used to show feet up close, prolonged, in slow motion, and, in some cases (particularly involving an injury), in your face and bleeding. Not that this is a bad thing. Absolutely not! Tarantino makes an effective masterpiece of cinema and artistic motif of it in nearly every movie he makes. Perhaps McCarthy does the same with intent in all of his films (albeit with less style and success as Tarantino), with the “sole” purpose of showing feet and nothing more. I’ll have to check out more of McCarthy’s films to find out. While the 2011 short film of The Pact lacks a comparable sideshow of barefoot women, it does have the film’s Annie counterpart, Jewell Staite, barefoot in the kitchen. Just a coincidence? What do you think?

Yes! That’s Annie in the hallway, with an injured bare foot…of course!

As another side note (not at all affecting the film overall), The Pact (2012) has some benign but obvious errors in continuity, not at all related to feet. Oddly, they all occur in a scene involving the use of a Ouija Board. Watch as Annie’s fingernails go from au naturel to glossy and back several times while touching the board. Also watch how a cross attached to a chain is suddenly unattached from the chain, from one scene to the next, without even supernatural assistance. Although most movies have some such issues (many of which I don’t even notice), I did notice those.

With a close-up of Caity Lotz’s foot (with pink toenails visible), my point is well made? But, keeping with the movie’s theme, I’m not finished!

And while I rarely include comments about a movie’s title, I will with this one. I like titles that reference the movie’s plot and ultimate meaning in cryptic, ambiguous ways, leaving it to the viewer to fill in the blanks. The Pact, however, has absolutely no connection to the movie that I can think of…but I’m still thinking. A pact, defined as “a formal agreement between individuals or parties,” simply does not exist in the movie in any way, even by any stretch of imagination I can make. If you see it, please let me know in the comment section below. Creative thinking is always welcome…and certainly necessary here!

Claustrophobia and fear of closets counterbalance foot fetish joys galore in The Pact.

CONCLUSION

While the short to feature transfer is less than perfect, losing effect in revealing too much, it’s still satisfying as a lesser-known gem in need of a polishing. If you can get it for a deal, it might even be worth adding to your collection (especially if you like feet). And, if anyone knows the meaning of the title, how it connects to the films, don’t forget to let me know; leave your thoughts below in the comments…please. Perhaps I missed something. Keeping with the movie’s theme, the mysteries and meaning around us are sometimes more obscure and elusive than they should be. Sometimes, the most horrible things are hidden around us everywhere, not far away. But, sometimes the feet are more than obvious…

A late-night trip to the soda machine at Motel 8, barefoot in short shorts! (While this screenshot stops at the ankle, the movie goes all the way.)

And, of course, let’s ride that motorcycle barefoot!

Rocket Rating – 6

Chris Rennirt (the author of this review) is a movie critic and writer in Louisville, Kentucky, as well as editor in chief at Space Jockey Reviews. He has been a judge at many film festivals, including Macabre Faire Film Festival and Crimson Screen Film Fest, and he attends horror and sci-fi conventions often. Chris’ movie reviews, articles, and interviews are published regularly on Space Jockey Reviews and in Effective Magazine. His mission statement (describing his goals as a movie critic and philosophy for review writing) can be found on the “Mission” page, here at SJR. For more information about Chris Rennirt (including contact details, publicity photos, and more), click here.

You may also like these!